“I am not Carl Dreyer, and I should shut up”

Thursday | November 19, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here:

So says director Guillermo del Toro in his self-deprecating lead-in to his audio commentary on the great Danish filmmaker’s 1932 classic, Vampyr. Fortunately he did not act on his words but goes on to give an erudite, often personal series of insights into the film.

Owners of the Criterion boxed-set edition of Vampyr (2008) may be wondering if their memories are playing them tricks, since its audio commentary was done by our good friend Tony Rayns. Tony’s comments are on the Eureka! edition of the film (also 2008), too, but the British label got del Toro to sit down and record an exclusive second commentary. British websites reviewed the disc, but I suspect that many film fans in other countries are not aware of the existence of del Toro’s commentary.

Early in that commentary, the modest, humorous tone continues, as del Toro says his remarks are “The equivalent of inviting a fat Mexican to your house and feeding him, and then you have to listen, for mercifully a short time, and then disagree, agree, insult, or share any of my opinions.”

From that point on, though, del Toro gets serious. He has worked in the vampire genre himself. His first feature, Cronos, is a vampire tale of sorts, and in June he and co-author Chuck Hogan released The Strain, the first novel of a trilogy that treats vampirism as a fast-spreading virus. Beyond these works, however, del Toro knows an enormous amount about the history of the vampire genre.

For the most part, his comments don’t follow the action on the screen. He begins with a lengthy disquisition on the skull imagery and its creation of a memento mori motif. At times the subject under discussion syncs up briefly with the unfolding narrative. As the protagonist, Allan Gray, watches reflections in a pond that have no visible cause, del Toro discusses the nature of Dreyer’s take on the genre:

In strict terms, it is perhaps one of the few vampire films that have actually gone to the root of the mythos and made the vampire a spirit, not a physical creature. Most of the time you get a living corpse . . . And in the oldest European tradition, in the most antique manuscripts in Eastern Europe and Greek manuscripts about vampirism and so forth, in reality it is a spiritual infection. The vampire is a hungry spirit that will drain the living and will of choice materialize partially and selectively if it needs it, if it serves him so. But essentially a vampire is a shadow and the father or the mother of shadows. It is this hungry shadow that haunts the living and drains them.

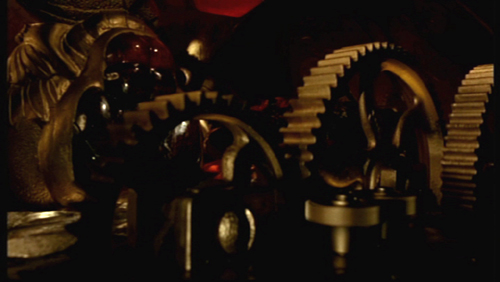

Del Toro clearly loves Vampyr and stresses its influence on him. Seeing Gray as a Christ figure, he named the protagonist of Cronos Jesus Gris (Spanish for “gray”) as an homage. He copied the cracked gravestone of the vampire in Hellboy. In discussing the shots of the gears of the milling machine that kills the villainous doctor at the end of Vampyr (above), he remarks, “I have myself tried to reproduce the beauty of those gears, incessantly and not very fruitfully I may add, but I try for sure.” (See below.)

Del Toro also remarks that there is no reason that characters in vampire stories—or other kinds of stories—must be nuanced. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences may prefer to reward actors who play complex characters. Still, he sees no reason why in Vampyr the doctor needs to be anything other than evil, the hero anything other than spiritually pure.

Del Toro refuses to try and interpret the film’s symbolism, saying that decoded symbols become “ciphers.” He continues:

It is foolish to try to decode the symbols in Vampyr. It is important to understand the rhythm and the repetition of them. And it is important to try and talk about them in the most general sense, but one should not foolishly try to assign specific value to them, because in doing that you would asphyxiate the poem, you would asphyxiate the film.

There is relatively little discussion of film style, but at about 49 minutes in del Toro talks about camera movement and how it creates mood rather than strictly serving the narrative. He challenges his auditors to examine films shot at the same time (in 1931-32) and find three or four other films that were experimenting with camerawork in this way. He even gives one of his email addresses so people can write and give him lists of titles that might contradict him. (With The Hobbit script in progress and pre-production already begun, I suspect that del Toro is not checking that particular address—which he reserves for fans—as often as he used to.)

There are other interesting points, as when del Toro suggests that Dreyer was influenced by Un chien andalou. Not that he created a surrealist vampire film but that he felt freed from the necessity to follow a narrative closely. To del Toro, the underlying plot of the film is simple and easily comprehensible, leaving Dreyer free to devote much of his film to a more poetic, evocative style.

The Criterion and Eureka! versions share several of the same supplements, including a 1966 documentary on Dreyer’s career, a “visual essay” by Casper Tybjerg on Vampyr, as well as the original Sheridan Le Fanu story on which the film was loosely based (in pdf form on the disc in the Eureka! version and in a booklet also containing the original screenplay in the Criterion one), and improved English translations. Criterion has included a 1958 radio broadcast of Dreyer reading an essay on filmmaking, while Eureka! provides two deleted scenes that were removed by the German censor before the film’s premiere. These scenes are not entirely unfamiliar, since they remained in the French version. The Criterion rendering of the film seems to have boosted the contrast, perhaps too much. The Eureka! version’s gray, misty visuals look more like those that I’m familiar with from reasonably good 35mm copies.

For a detailed comparison of these two releases and the older Image edition (1998), see DVD Beaver. For a review of the Eureka! disc, supplement by supplement, see DVD Outsider.

As with other Eureka! DVDs, this one is region 2 coded.

Cronos